Remembering Flora on Mother's Day

She would have thought the fuss silly but enjoyed it thoroughly

I don’t recall ever celebrating Mother’s Day as a child. Or maybe I do, but it wasn’t for my mother. We used to visit my grandmother Edith, my father’s mother, in Berkeley (she was Oma to us) and usually brought her a flowering plant. But, as for my own mother, I don’t believe there was any such commemoration in her native Scotland. And growing up as poor as she did, a day devoted to mothers would have earned a shrug and perhaps one of her offhand remarks.

“Why a special day? I’m a mother every day.”

Secretly, though, I think she would have thoroughly enjoyed being celebrated, though, in her usual self-deprecating way, she would have acted as if none of it really mattered.

Although I’ve written about my mother several times in this space, it’s mostly in relation to food. After all, the place where I spent the most time with her was in the kitchen and my writing about her reflects that relationship and sometimes the ambivalence I felt about it and her.

I named a sourdough starter after her early in the pandemic. I pondered my love-hate relationship with cooking and its connection to the stereotypical idea of a woman trapped in the kitchen in another piece and how I wish I’d been closer to my mother in yet another.

I’ve written about her notebook filled with recipes, many stained beyond deciphering, about her signature pound cake with chopped candied ginger, and a European plum tart that she and many female relatives made for many a holiday gathering.

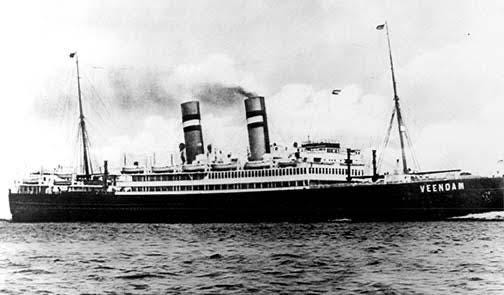

What I didn’t write about my mother—and really didn’t know—is who she was outside that kitchen, both before and after marriage and children. Like most kids, I was interested in Mom mostly in relationship to myself and didn’t spend much time wondering about the hopes, dreams and ambitions she might have harbored prior to boarding a ship for the U.S. in 1948, along with a husband and two young sons, leaving all she knew behind.

With another Mother’s Day upon us, it seemed as good a time as any to think about what I did know about Flora Gordon Stroud and what I might be able to find out. Helping me do this was a recently discovered transcript of an interview I did with her in 1990, shortly before she turned 74.

She told me that her mother, Leah, one of five children, came to Scotland as a small child and didn’t remember anything about the country of her birth. She spoke fluent Yiddish, the lingua franca of Eastern European Jews, as well as perfect English despite having had only about two years of formal schooling.

“She was a very intelligent woman,” my mother said. “She used to love poetry. And she loved to read.”

I wish I could find the original audio of my interview so I could hear the Scots accent that never left my mother’s speech, though she insisted that after so many years in America, it had faded. What I wouldn’t give to have a recording of her reciting the poetry of Robert Burns, which she adored. It was a hoot and a glimpse of a playful mother that I seldom saw because she was usually too busy catering to the needs of four children and my demanding father to share that mother with me.

(For a gorgeous reading of Burns’ “To a Mouse” by actor Sir William “Billy” Connolly, see the bottom of this post.)

My mother had scarcely traveled outside her native Glasgow until she left at age 32 with her husband and two little boys in 1948 to come to America to stay with my father’s family in Berkeley, California while he searched for a job as an engineer. She didn’t talk much about her early years and, like most immigrants, just tried her best to adapt to life in America, especially, to my father’s somewhat intimidating German-Jewish family that had fled the Nazis and immigrated to the U.S. a decade earlier.

My mother was also the daughter of immigrants—Lithuanian Jews who separately fled their country in search of a better life, met in Edinburgh, settled in Glasgow and raised five children. All of them were given English names: Albert, Hannah, Emma, Flora and Lily. Unlike my father, who was born into privilege in Germany, but then was forced to flee when the Nazis came to power, my mother grew up with almost nothing, beginning life as part of a family of seven in a house she described as a “one-room-and-kitchen.”

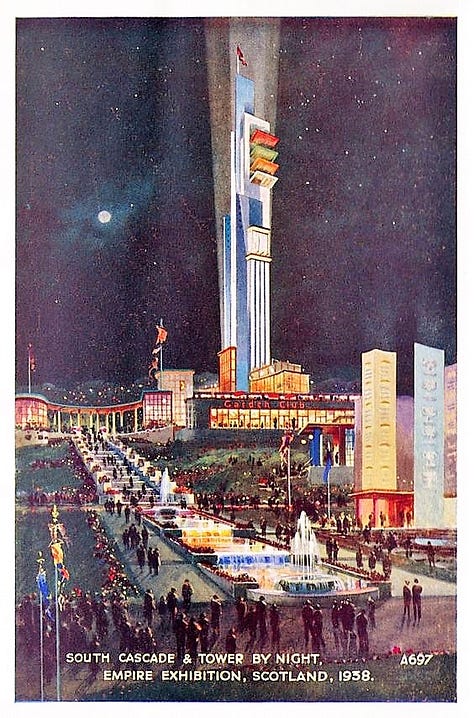

Mom left school at 14, taught herself shorthand (I still have two of the Gregg Shorthand books she must have used, and it looks impossible!), had a series of fascinating jobs, including working for a bookmaker (taking bets by phone directly from the race track!), a furrier who helped smuggle Jews out of Germany, and as a shorthand typist at the Empire Exhibition in 1938, akin to a Scottish World’s Fair, where she helped put together the official guide and catalog. That’s where she met my father, who was studying engineering in Loughborough, England at the time and ostensibly came to check out the Engineering Pavilion—and discovered my mother! (Shortly thereafter, he was sent to an internment camp in Canada before being released to join the British Army—but that’s another post.)

Flora Gordon, was born on March 18, 1916 in Glasgow, Scotland, to Leah and Kushiel Gordon, both Lithuanian Jewish immigrants. Leah, whose maiden name was Bloom, was born in Kovno, Lithuania, which later became Kaunas. It had had a vibrant Jewish community that had been there for some 400 years and was almost completely wiped out during the Holocaust, as was the majority of the Jewish population in Lithuania and elsewhere in Eastern Europe.

My Grandparents

I only met my grandmother Leah once when I was six and accompanied my mother to England and Scotland for the summer. Unfortunately, she was already suffering from dementia. I loved her anyway. I remember delighting in walking out of the room and returning to hear this fuzzy-haired old lady with large wondering eyes asking, “Who’s the wee girl?” “I’m Ruth, grandma,” I would say. “Don’t you remember me?”

Leah’s father, Solomon Bloom, a widower, remarried and had two more children, her half-sisters. The family lived in Edinburgh, and that’s where Leah met my grandfather. One of the stories I heard was that the pair were fixed up, which probably would have made sense in those days, but I can’t verify it.

Kushiel Gordon (probably changed from Gordonovich) was born not far from my grandmother, and his family sent him to Scotland at age 17 so he could avoid being drafted into the Russian army (Lithuania was under Russian control at that point). Being drafted into the czar’s military was a common fate for young Jewish men in those days—and it usually didn’t work out very well for them.

In Edinburgh, Kushiel went to work for a man who dealt in Oriental carpets and became a traveling salesman selling rugs to wealthy folks in Northern Ireland.

“He used to go away for three weeks a month, but he always came home for Jewish holidays. Always,” my mother said.

He was also a good cook, making the Jewish dishes he remembered from home, like kreplach (filled dumplings). He played bridge and other card games with his buddies in the kitchen, which is where my mother slept in a tiny alcove. (Sadly, I never met my grandfather; he dropped dead one day in 1936 when my mother was only 20.)

I’m sure the language Kushiel spoke with his card-playing cronies was probably Yiddish. I didn’t realize that my mother actually knew the language until many years later when my sister-in-law (another Ruth Stroud!) told me that Mom was chattering away to her parents, who also spoke Yiddish.

Yet my mother never let on to us that she could speak “Jewish.” Why not? I’m pretty sure she worried that my father’s more aristocratic German-Jewish relatives might consider her knowledge of what they viewed as a sort of “bastardized German” (Yiddish, essentially a form of German, with some Hebrew, Russian and Aramaic words thrown in, is usually written with Hebrew letters) marked her as lower class. And yet my mother, a huge reader and excellent scholar who eventually went on to get a bachelor’s degree from San Jose State at the age of 60 (the only one in her family to do so, I believe), was an avid reader of Yiddish writers like Sholom Aleichem, creator of Tevye the Milkman, central character in the famed musical Fiddler on the Roof.

Today there’s a resurgent interest in Yiddish, and the community of speakers of the language has increased. Urgent efforts are going on to preserve the rich culture inherent in Yiddish literature, recipes, music and the language itself, once spoken by a estimated 11 million people prior to World War II. Sadly, I don’t speak much Yiddish beyond the usual schlemiel, schlimazel and meshuggena, but I’d love to learn. I only wish my mother was around to teach me.

Although I obviously can’t ask her anything, I’ve opened a few drawers and started a few online searches and even connected with the daughter of one of Mom’s cousins, a woman who is also called Ruth (there seem to be quite a number of us in the family!) who still lives in my mother’s native Glasgow. I hope to glean more information about Flora’s family tree. Stay tuned!

Mothers, even when they’ve been gone for going on 24 years, leave their mark. Mine might have been the reason I started writing this blog—to bring the place where I knew her best, her kitchen, closer since I couldn’t have her.

Happy Mother’s Day to all the moms out there—and don’t forget to call yours or, better yet, go see her today.

Thanks as always for reading and spending time with me. If you enjoyed today’s newsletter, please tell your friends—and me too!

Ruth

PS: Here’s a little something for your listening pleasure!

I really enjoyed reading this piece!

What a lovely read this was. I love that you are delving into your mother's past this way--it feels like we as daughters should know our mothers best, but it's easy to think of them only in relation to ourselves rather than as multi-dimensional people who existed before they had children! Looking forward to hearing more of this story.