From Nazi Germany to the Beach: Travels of a 300-year-old Clock

🕰️ Family heirloom ticks back to life after a 15-month silence

While food is my usual subject, I’m taking a break today to write about a remarkable clock, almost 300 years old, that has recently come back to life in my living room.

It arrived at the start of the pandemic in March 2020—a giant “longcase clock,” as it’s sometimes called, in several pieces wrapped in bubble wrap and cardboard. It was the family grandfather clock, come to me all the way from my cousin Alan’s house in Denver after a life change made it impossible for him to keep it. Its history in the 100-plus years my family has possessed it stretched across some 11,000 miles of land and sea, from Karlsruhe, Germany, to San Francisco via the Panama Canal, to my grandparents’ home in Berkeley, to my aunt and uncle’s residence up the street, to Denver, then back to California, this time south to our house near the beach.

“Each move,” as my cousin Tina wrote in a piece published in the Santa Monica College Emeritus publication, “was initiated due to a seismic shift; A looming genocide, a death, or a divorce.” And almost no one wanted to take on the responsibility of a complicated, fragile, slightly damaged, very heavy object that needed to be wound every eight days, not to mention cleaned and oiled by an expensive specialist every few years. Every so often, it got out of sync and sounded the hours at the wrong time—or stopped altogether.

Neither Alan’s sister Tina nor his brother Hal wanted the clock, but they thought it might be a good fit in my living room, already filled with family memorabilia and furniture and with a ceiling lofty enough to accommodate a clock measuring more than 8 feet in height, with another foot of decorative finials at its peak.

So I reluctantly agreed to take it, already wondering who would want it after I was gone. The likelihood that our only child Sam and his wife Nagisa, currently residing in a tiny, minimalist apartment in Japan, would claim it was slim to none.

But how could I refuse to take the familiar talisman of childhood that I’d known from countless visits to my grandmother Oma’s house in Berkeley? There it had sat in the entryway next to the staircase, a witness—and sometimes victim—of the sliding legs of a generation of boisterous grandchildren (18 in all!) that often hooked the wooden figures (two angels and Atlas, the mythical Greek god who carries the celestial globe on his back) atop the clock and sent them crashing to the floor.

My cousin Tina wrote about a memory that echoed my own:

“We would swing our legs over the banister, and balance on the top of the clock to begin our descent. I remember hearing a crunch after my foot came down on it, probably cracking its top.”

We cousins—the offspring of my grandparents’ five children—gave that clock scant attention in those days. We much preferred an ornate chest with brass handles whose top drawer concealed bags of M&M’s that Oma kept for us—and herself.

Escaping with the family heirlooms

The clock and the chest were just two of many pieces of heavy mahogany furniture that my family had somehow spirited out of Germany when they fled from the Nazis in late 1938, right before the doors slammed shut on Jewish emigration. They were among the lucky ones who got out, just a few weeks before Kristallnacht, “The Night of the Broken Glass” when Jewish-owned businesses and synagogues were looted and destroyed in a government-orchestrated pogrom.

How they managed to sneak out so many enormous pieces from their well-appointed home in Karlsruhe while running for their lives was never made clear and, as a child, and even later as an adult, I never thought to ask.

And, why, for God’s sake, bring an enormous, very heavy clock? Why bring any of it?

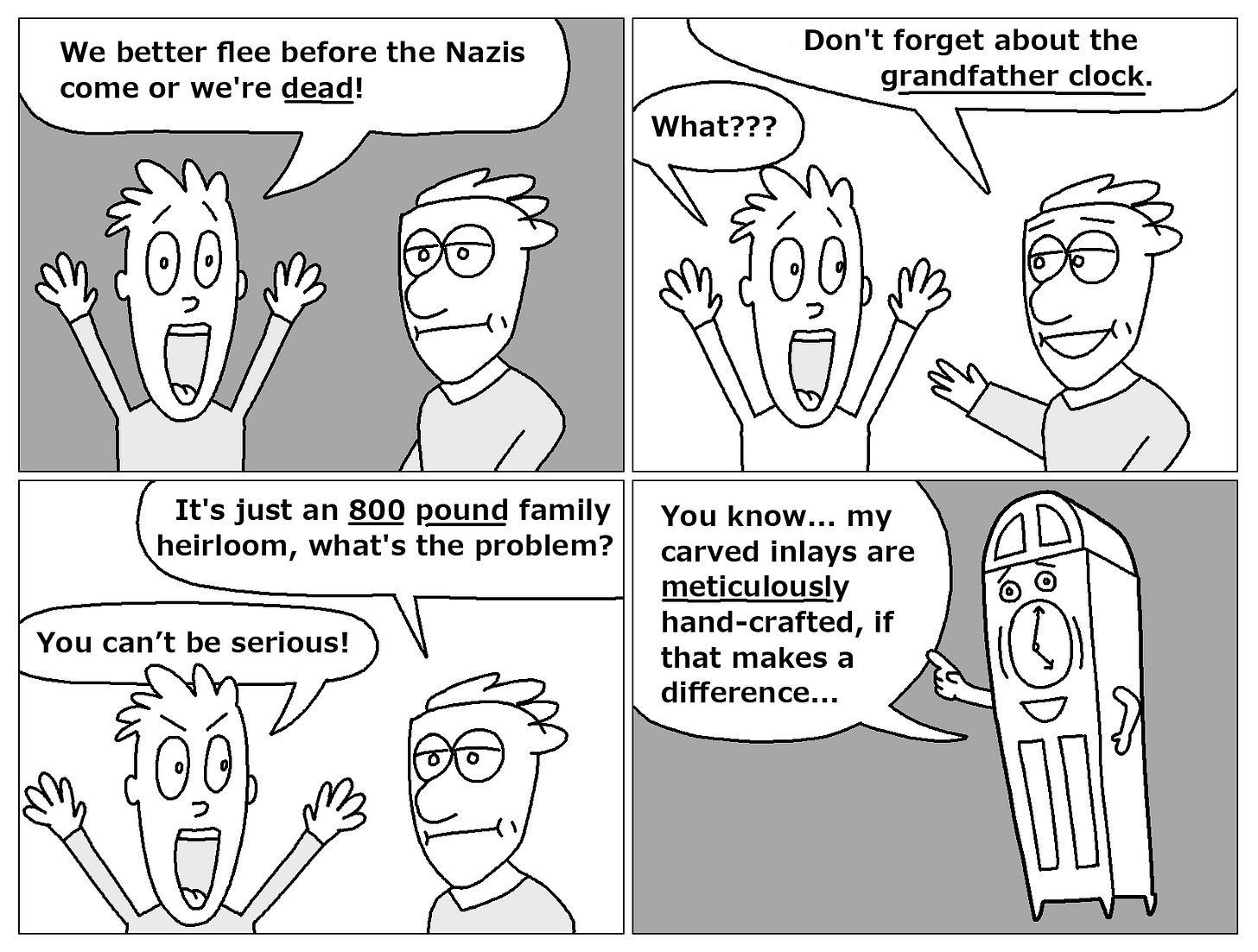

When I asked my son Sam to draw a cartoon for this newsletter, he had the same thought.

“I would be the guy (in the comic) who’s freaking out,” he told me. “I’d say, ‘Screw the clock! There’s not going to be any heirlooms if we’re all dead! Give me the next boat out of here!”

Waiting for the Clock Man

I had my doubts too about the clock as the months ticked by and the giant empty clock case sat like a mute giant towering over the living room. Its glass-fronted top was empty of its ornate brass face, which sat on the floor, along with the brass weights and pendulums. Everything was still encased in plastic, which Jackie, our frisky new kitten, took great pleasure in clawing and chewing to bits.

The wooden angels, each minus a wing, seemed emblematic of our captive condition. Would we ever take to the skies again?

Shortly after the clock had arrived last March, I’d found the perfect person to set it up—Bill McIlvaine of Grandfather Clock Repair LLC. Could there be a more promising name? On the phone, he said he’d had more than 30 years of experience fixing all sorts of clocks and thought this one would present no problems he couldn’t solve. We made an appointment. But then came the lockdown.

“I’ll call you in a few weeks,” I told Bill as I canceled the appointment.

Then we waited. And waited. Months passed. And then a year. In March 2021, I called Bill again. “Are you ready to fix my clock?” I asked.

“I’m not vaccinated yet,” he said. “I’ll let you know when I am.”

And finally he called. He could come in early June. Hurray! During the pandemic, he’d moved from downtown Los Angeles 60 miles north to the coastal city of Oxnard. He hadn’t worked in a year, but he had all his tools and was excited to be back in business again.

Fixing clocks was Bill’s passion—and a lot more fun than his previous career career managing a small AM station in Wisconsin.

He’d found his calling in 1991 after a high school friend offered to train him over the course of a weekend. “And that’s how I got started—and I just kept going.”

Working on clocks makes him feel a bit like a magician,” Bill told me.

“Usually I walk in the door and the clock isn’t working and, by the time I walk out, it is.”

Clock whisperer Bill McIlvaine solves a few mysteries

And finally, after 15 months, Bill McIlvaine was in my living room. At six-foot-eight, he was almost as tall as my clock, certainly a plus for placing those broken finials back on top!

Despite some damage—mostly cosmetic—the clock had been well maintained and was still in good shape, he said. And it is far older than any of us had imagined, probably pre-dating 1750, before the American and French revolutions and the Industrial Age. Bill knew this because of its brass face; after that date, clocks usually had white faces, considered easier to read. This was news to me. As far as I knew after quizzing my cousins, the clock was possibly a century old or so, acquired by our grandparents, or perhaps their parents. But who owned it before that? That was another mystery we couldn’t solve.

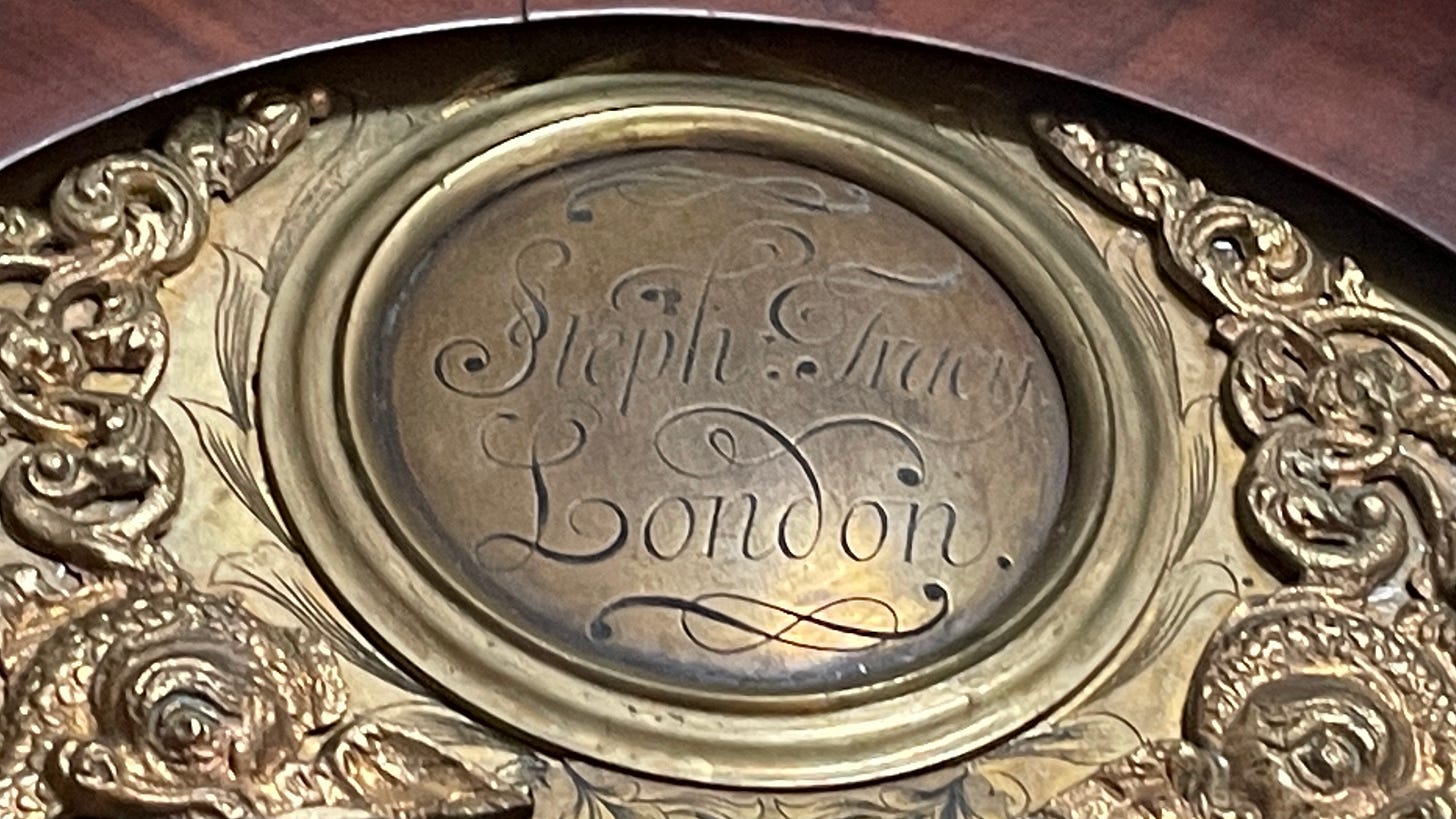

We did know it was made in London by someone called “Steph Tracy”—perhaps Stephen Tracy. An an ornate inscription on the front said as much. But a Google search didn’t yield much information about this man. Bill said that Tracy would have been only one of the people who contributed to creating the clock.

“Typically the way London (clockmaking) worked (in the early 18th century) was that, for instance, somebody would make the bells, but not Steve Tracy, and somebody would do the dials and put Steve Tracy’s name on it, but not him personally because it was kind of a different craft. What he would do was put the whole thing together in a cabinet that was made to order, and then he would produce this movement.”

It would have been state-of-the-art technology for its time, he said, some 500 years in development before the complicated system of telling time using brass weights, pendulums, gears and bells came to fruition.

Now that it has been set up, it has been hard not to fall in love with the clock. After a few adjustments, it keeps almost perfect time and even shows the day of the month in a small window.

I keep discovering small details I didn’t notice at first, like the tiny faces sculpted into the baroque brass swirls at its corners.

Another nice thing is that during power outages—fairly frequent in these parts—it will likely keep on ticking. And, when the earth starts shaking, as it inevitably does in California, hopefully the bolt in the wall will keep it upright and its tinkling treble chime will continue to delight the ear—except when the switch is turned from “Strike” to “Silent” at night.

Another mystery I cannot solve is where the clock’s travels will take it next. Japan? Paris? Our children don’t want to be encumbered with so many heavy possessions as they embark on life adventures far from where they were born. Their residences are small and spare—apartments or houses with little furniture, and most of that lightweight and impermanent. What would they want with a towering museum piece that my cousin’s daughter refers to as “a bonkers object”?

But hopefully, one of the our offspring will one day find room for a beautiful clock with a very long history.

It’s a great clock and well worth keeping, according to Bill McIlvaine.

“If you get it cleaned and oiled once in a while, it’ll go another 100 years, easy.”

Who knows what the clock will have witnessed by 2121? I’m hoping for a hospitable future not only for the clock but for us all.

I loved reading this, Ruth—What history! Beautifully written and the clock is WOW! I’m sure its story will continue for another hundred years and beyond.

Glad I got to see this historic clock and now hear the story behind it. How great to dust off your memories of family stories because of the clock. It's absolutely beautiful and I love how you have rediscovered it and explored new details. I hope you find someone in the family to bequeath it to, but if not, maybe some historical group or museum would give it a good home for centuries to come.