Food: The Universal Cure?

Family tales stir memories, worries and a yen for blueberry muffins

Can food cure the world’s ills? My grandma apparently thought so. The famous story I’ve been told—with multiple variations—is of my cousin Dan taking her car for a spin when he was a teen and hitting a tree (in another version, he hit a policeman’s car). When he returned to her house, shook up and sure of a reprimand, her first words were, “Poor boy, you must be hungry.”

My grandma, whom we called Oma, was a very large woman who had her dresses—usually covered in small blue flowers that matched her eyes—specially made to fit her enormous bulk. But to me she was the source of endless amounts of food and generosity. I knew, as did most of her 18 grandchildren, that when I entered the front door of her home in Berkeley, just a few blocks down a hill from the Claremont Hotel, after a requisite hug for Oma, there was a carved mahogany chest in the foyer with a top drawer filled with candy—including a big bag of M&M’s that we happily plundered.

Somehow that sweetness, those brightly colored candies spilling everywhere, the many cream cakes in pink boxes from the Eclair Bakery on Telegraph Avenue that filled the fridge, the chocolate covered coffee beans in little crystal bowls in the living room, the long dining room table with its snowy cloth, covered at meal times with silver platters and china somehow rescued from the Nazis when the family fled their hometown in Karlsruhe, Germany in 1938, stood for something more significant than simple nourishment. They personified comfort, security, abundance, and ultimately survival—for, had they not escaped from Hitler’s Germany, none of us would be here to tell the tale.

I never got to know my grandma as an adult. She died when I was 17 and is buried in the same cemetery in Oakland where we laid my cousin Hal to rest earlier this month and my cousin Dan two years ago, and where so many of my relatives are buried. That’s comforting too somehow—I’m not a big believer in the afterlife, but it’s nice to imagine them joking, gossiping, kvetching (complaining), maybe having a drink together and tut-tutting about the foibles and follies of those they left behind.

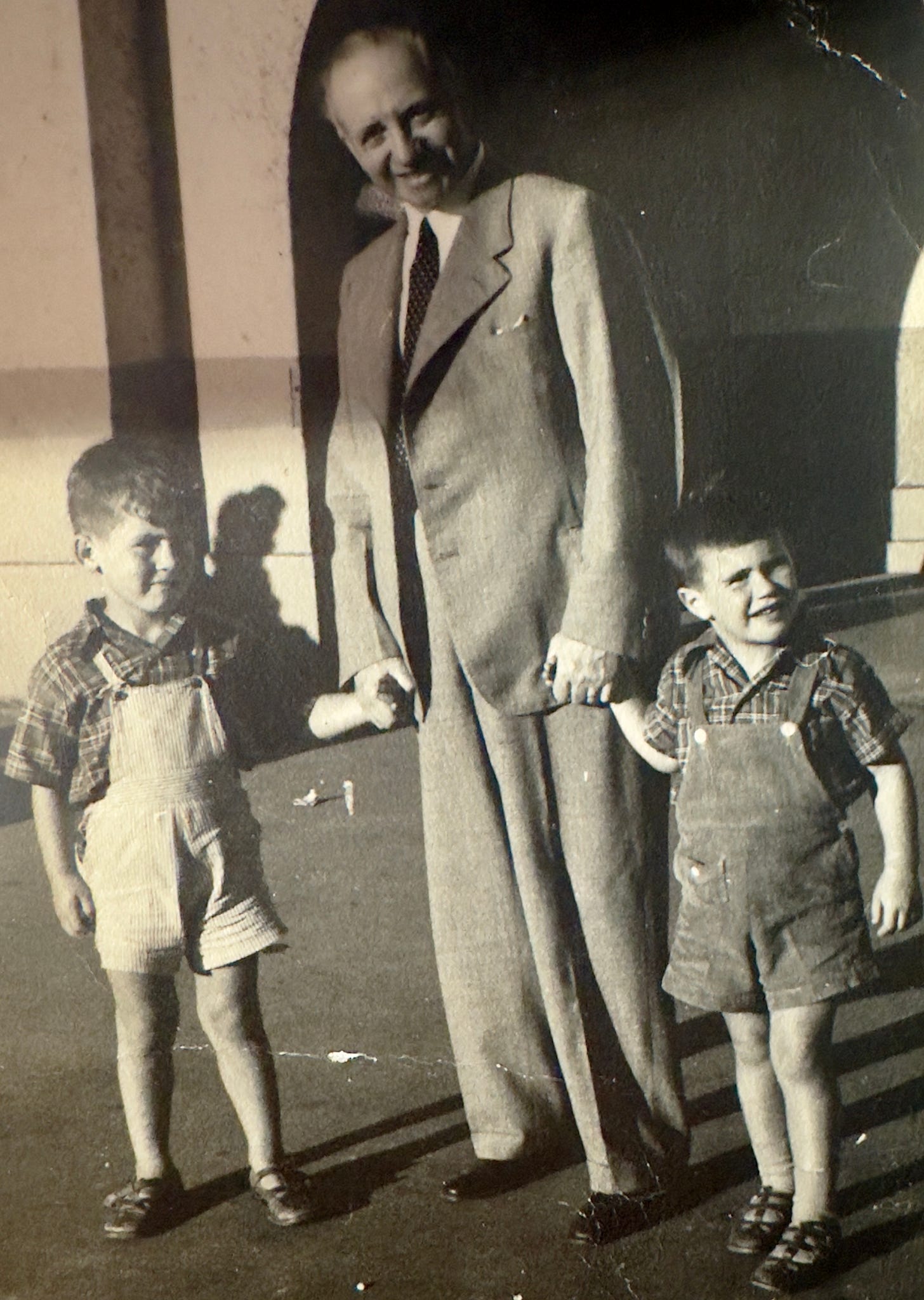

Why am I writing about this now? Perhaps it’s the enjoyment of escaping into memory while trying to tamp down worries about the current situation in our country, where national borders are again becoming war zones and immigrants and historic allies are regarded with suspicion or outright hostility. At this moment, I can’t help but wonder what my father, aunts, uncles, Oma, and yes Opa, my grandfather Friedrich (later Frederick) Straus, who died a year after I was born, would have to say. Would they be surprised at the situation, or would they find it all too familiar?

While Oma might invite us to another generous and soothing meal and chide us when we put down our forks to take a breather, my grandpa Fritz would probably suggest action to hold our country to account and make it live up to its democratic principles. The third-generation principal of a bank in Karlsruhe, in partnership with his two brother-in-laws, Opa had served in World War I on the German side, heading to battlefields in 1914, the same year he married my grandmother Edith.

Many German Jews served on the front lines of the Kaiser’s army yet faced charges of disloyalty after the war. (In another irony of history, my father, who left his birthplace in 1935 at age 17, two years after Hitler came to power, served in the British Army with the Allies in World War II, after first being imprisoned as an enemy alien in Québec, Canada.)

After the family escaped Germany via Switzerland, Opa shepherded his wife and daughters first to New York and then to the west coast of the U.S. through the Panama Canal to San Francisco, where he had friends and contacts. They eventually settled in Berkeley, and my grandfather became an associate of the Bank of America in San Francisco. He also became a proud patriot deeply loyal to his adopted country despite being at first classified, like my dad, as an enemy alien, during the war. Unlike Japanese Americans, our family was never herded off to an internment camp because of its heritage, although my father did suffer that fate at the hands of the British in 1940 before the government relented and decided German Jewish boys might make useful soldiers in the war against Herr Hitler.

Mindful of his good fortune, my grandfather gave a number of patriotic speeches including one at a service organization called the Berkeley Lodge on May 27, 1942 at a dedication for the American flag. In it, he praised the values for which the flag stood, suggesting it should be a call to action to the members in a perilous time.

“This flag was not given to us as a dead symbol, but as a challenge to inspire our life and the life of the nation with the teachings of the past and the hopes for the future. Remember, friends, that real freedom can only be won and defended by those who never forget the suffering of their brothers and sisters in distant lands. …They look to us in this free country to bring them spiritual and actual help for their liberation.

“In this spirit, I dedicate to you this our flag, in the name of our refugee friends who, like myself, have the earnest desire to become co-workers and co-builders in your midst, in the hope that our erroneous classification as ‘enemy aliens’ will soon be taken away from us, so that we, as America’s most grateful and most loyal friends, can fully contribute our share to the blessings of this land of liberty.”

We were the lucky ones. There were others here already to vouch for us and prove to the American government that our family was financially solvent and wouldn’t be a burden on the U.S. taxpayer. Grandpa got a job to help support his family. He sent his young daughters to school. My father’s younger brother Irwin served in the U.S. military, where his skills in German were put to good use.

My family had the means to help itself, but many immigrants who seek refuge in this country now don’t. Yet, unlike some of those with wealth today, my grandpa felt his money conferred a special obligation to help others who were less fortunate—especially his fellow Jews who were in desperate circumstances in Europe as Hitler’s noose drew tighter and the Final Solution—the decision to systematically murder the Jews of Europe—was put into effect.

My grandparents, parents, aunts and uncles managed to create a wonderful life in this country for themselves, their children and grandchildren, but in another ironic coda, members of both my generation and the next have reclaimed their German citizenship in order to leave an increasingly divided and angry America and return to Europe in search of that elusive dream my grandfather once found so promising. With the rightward trend in European governments, including Germany, it’s not at all certain that they will find what they’re seeking.

As for Oma’s idea that food can cure all ills, I’m not one to let that message go to waste. In a time of worry and sorrow, sharing a meal with relatives, friends, and new acquaintances has been a great solace. We just took a short trip to Galveston Island in Texas, sampled some gumbo and freshly caught seafood, met a personable king penguin called Athena at the local aquarium, and braved the unusual cold spell that blanketed the area to discover the charms of this historic Gulf Coast destination. I’ll be writing more about that in the near future.

Muffin therapy

Meanwhile, as promised in a previous post, here’s a blueberry muffin recipe I’ve made several times and now view as an essential morning (or afternoon!) comfort food, along with the blueberry buckwheat pancakes from the same source—Anne Byrn’s Baking in the American South: 200 Recipes and Their Untold Stories, one of my new baking bibles that is also filled with delightful tales and lore. I suggest you buy the book today and then subscribe to Anne’s terrific blog, Between the Layers, which supplies more of the same engaging mix of recipes and stories.

The blueberry muffin recipe is deceptively simple, but the amount of fresh berries—2 cups—make it a particularly irresistible blue-tinted morning treat. I like to sprinkle the little cakes with coarse sparkling sugar that delivers a sweet and satisfying crunch when you bite into them.

The recipe comes from Anne’s friend, a former editor of the Savannah Morning News, Martha Giddens Nesbit, who likes to serve the muffins with pan-fried flounder, cheese grits and salad. I’m quite happy with a simple muffin, slightly warmed, possibly with an additional slick of blueberry jam, a perfect accompaniment to a cup of milk-laced Irish Breakfast tea or dark-roast drip coffee. That’s my idea of comfort food. It might be a little too spare for my German grandma’s taste, but my Scottish mother would approve.

Martha Nesbit’s Blueberry Muffins

(Very slightly adapted* from Baking in the American South by Anne Byrn)

Makes 12 muffins

Ingredients:

Vegetable oil spray for misting the pans or paper lines

8 tablespoons (1 stick/114 grams) unsalted butter, at room temperature

1 cup (200 grams) granulated sugar, plus 2 tablespoons for topping (or substitute demerara sugar or coarse sparkling sugar for the topping)

2 large eggs

1/2 cup whole milk

1 teaspoon vanilla extract

2 cups (240 grams) all-purpose flour

2 teaspoons baking powder

1/2 teaspoon salt

2 cups (12 ounces/340 grams) fresh blueberries

Directions:

Heat the oven to 375°F, with a rack in the middle. Mist a 12-cup muffin pan with vegetable oil spray or line with paper liners.

Place the butter and the 1 cup sugar in a large bowl and beat with an electric mixer on medium-low speed until creamy, about 2 minutes. Add the eggs, milk and vanilla and beat on lowjust to combine. Turn off the machine.

Whisk together the flour, baking powder and salt in a small bowl and stir into the batter. Gently fold in the blueberries.

Using a 1/3-cup dry measuring cup or an ice cream scoop, divide the batter among the muffin cups, filling them nearly to the top. Sprinkle the tops with the 2 tablespoons of granulated, demerara or sparkling sugar. Place the pan in the oven and bake until the muffins are slightly golden brown and the tops spring back when lightly pressed, 25 to 30 minutes. Lift the muffins out of the pan carefully, and transfer them to a wire rack to cool completely, about 30 minutes.

Serve at once or let cool, then place in a zipper-top bags to freeze for up to 4 months.

*Note: I’ve tried subbing a half cup of whole wheat flour for the all-purpose and reducing the sugar to 3/4 cup. The muffins were still wonderful!

Thanks for your likes, comments, shares and subscriptions. It makes a world of difference to hear from you. Please let me know if you’re doing a lot of comfort cooking and baking lately and what you’re making.

See you soon!

Ruth

PS: Athena the king penguin sends you greetings from Galveston, Texas! She’ll have more to say next time.

Food definitely cures all ills. My latest "thing" is mastering croissants and they're GREAT for curing your body's butter deficit. Three sticks for the butter block and an additional 57 g of butter for the dough. All to make 8 croissants. Even without doing the math you can tell that's a LOT of butter per croissant. On the plus side, they're rather tasty ...

Thank you for sharing family memories and thoughtful observations about our scary times. Those muffins, with the added quantity of blueberries, look tempting. It's wonderful that you have so many family photos from an older generation. Love the crocheted dresses!