We’re heading to Barcelona and Sicily for a few weeks. I may share a few pictures and comments from our travels, but probably not a proper post until we return in late May. Part of the reason for the trip is a celebration (or reaction) to a big birthday. In the wake of that milestone, I’ve been doing some reflecting on my life and immigrant roots. Here’s a piece of it, with perhaps more to come.

“You were born in time for breakfast,” my mother told me. Beyond that, she didn’t remember much about my arrival in the world.

I don’t remember much either. A room I had to myself until a baby brother arrived 10 years later. Walls of knotty pine that sometimes morphed into a forest filled with wolves’ eyes. A framed picture of Little Red Riding Hood, her crimson hood barely concealing the flowing blond tresses beneath, nothing like my tangled dark brown curls that no one could get a comb through without making me cry.

A double glass door to a patio and a path to a garden with three fruit trees, a sandbox, lilac and rose bushes and pink lilies with a scent that summoned bees, tiny butterflies and me.

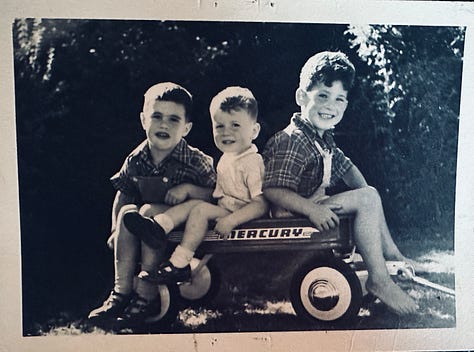

I was the third of four kids, born a year after my parents arrived in California from Glasgow, Scotland to live with my grandparents in Berkeley while my father hunted for an entry-level engineering job in the bucolic, orchard-filled peninsula south of San Francisco that later became known as Silicon Valley.

Some eight years earlier, in June 1940, my father’s engineering studies at Loughborough College in England had come to an abrupt end by order of the British government and its prime minister, Winston Churchill after Germany invaded France, then Holland, and threatened to do the same to England. In the panic that ensued, the government ordered a mass round-up of Germans living in Great Britain, making no distinction between Jewish refugees and Nazi sympathizers.

My father ended up being shipped across the Atlantic to Canada the day after another vessel, the SS Arandora Star, carrying other human cargo classified as “enemy aliens,” like himself, was torpedoed and sunk by the Germans. After a six-month stint in a detention camp in Canada, followed by six years in the British Army (the government decided that Jewish refugees weren’t a danger after all, and my father joined up immediately), Dad was trying to rebuild his life and career, and support my mother, whom he’d married while in uniform, and the two little boys who had been born in the succeeding years.

After returning from the war and completing his engineering studies and exams, there were few jobs to be had, so my grandfather, living fairly comfortably by then in the U.S., had suggested that my father try his luck in the San Francisco Bay Area. It seemed like the best choice; my father hadn’t seen his family in more than 10 years.

My Glasgow-born mother arrived with my 5- and 2-year-old brothers to live with my father’s parents while Dad went job- and house-hunting. My grandparents and their three daughters, my father’s sisters, had come to America 10 years before, fleeing Nazi Germany a month or two ahead of Kristallnacht—the night of organized pogroms when Jewish businesses and synagogues were systematically sacked and Jewish men and boys rounded up in the lead-up to the Holocaust.

My father had left his hometown of Karlsruhe, a few years earlier in the mid-1930s. At that time, he was an idealistic 17-year-old youth hoping to emigrate to what was then Palestine, considered a symbol of hope for many young German Jews who felt their future looked bleak in their homeland and elsewhere because of rising antisemitism.

I know little of Dad’s time in what later became the state of Israel—I think he was probably there for about a year— but I know the strict, pragmatic, intellectual, and sometimes difficult individual who was my father must have had a romantic, hopeful side to him in those days as he thought to remake his life while contributing to the birth of country that would be a haven for Jews who had never been really welcome anywhere else.

Did my father think about the Palestinian Arabs who inhabited the land too? I actually believe that he did, because I found titles of books in his library on the plight of the Palestinians, and I remember that he once gave a talk on the subject. But, 19 years after his death, I wish I had paid more attention to what he had to say and asked more questions. I know he would be heartbroken about what’s going on today in Israel.

While my parents had a great appreciation for art, literature and music, my father didn’t encourage any of his children to pursue creative endeavors as careers, hoping we would all go into the sciences or follow his lead into engineering—he didn’t think anyone could actually make a living in the arts. He was duly horrified when his two youngest children—my brother Michael and myself—pursued careers in journalism.

In his late teens, when he spent a year or so in Palestine and contemplated living there, my father must have enjoyed creating things with his hands, including this brass bookend with the image of a wide-legged worker holding onto a shovel and staring off into the distance. “Machar,” the word cast in Hebrew below the figure says. It means tomorrow, and I can hardly square it with my severe, firmly-rooted-in-the-here-and-now father. But clearly, somewhere behind that tough exterior resided an idealistic boy with a dream.

What does any of this have to do with my usual themes built around food? Not a lot, except that the meeting of cultures—American, German, Scottish, Jewish, Eastern European (my mother’s side)—and some of the traumas and healing built into going from households where food was plentiful and rich (my father’s) to wartime shortages and rationing (in Britain) to the bounty of California—affected my psychology, preferences and interest in diet and food.

Other than saying I was born in time for breakfast, my mother said she nursed me until I was almost a year, something she couldn’t do with her first wartime babies— and that I was the healthiest, but probably the plumpest, of her offspring. Food was always of central importance in our family, and wasting it was practically a sin, for the memory of going without was never forgotten.

I have continued that tradition, though I’ve been lucky enough never to want for sustenance, and in fact have wrestled with the opposite problem—how to cope with too much of a good thing. But still, the joy of discovering new foods, along with new experiences, has never waned. That’s as good a reason as any for our forthcoming trip.

So I’ll say arrivederci for now. Stay tuned for a few “postcards” from our travels.

Thanks as always for reading, liking, commenting and subscribing. Please don’t be shy—I love to hear from you!

See you soon.

Ruth

Ruth, I absolutely loving reading this and learning about you and your family! ❤️

Have a wonderful time abroad :)

Happy Birthday, dear Ruth. As always, I love seeing your family photos. Have a wonderful trip!