Did you know that many of the commercial breads we buy are essentially “indigestible gluten bombs”?

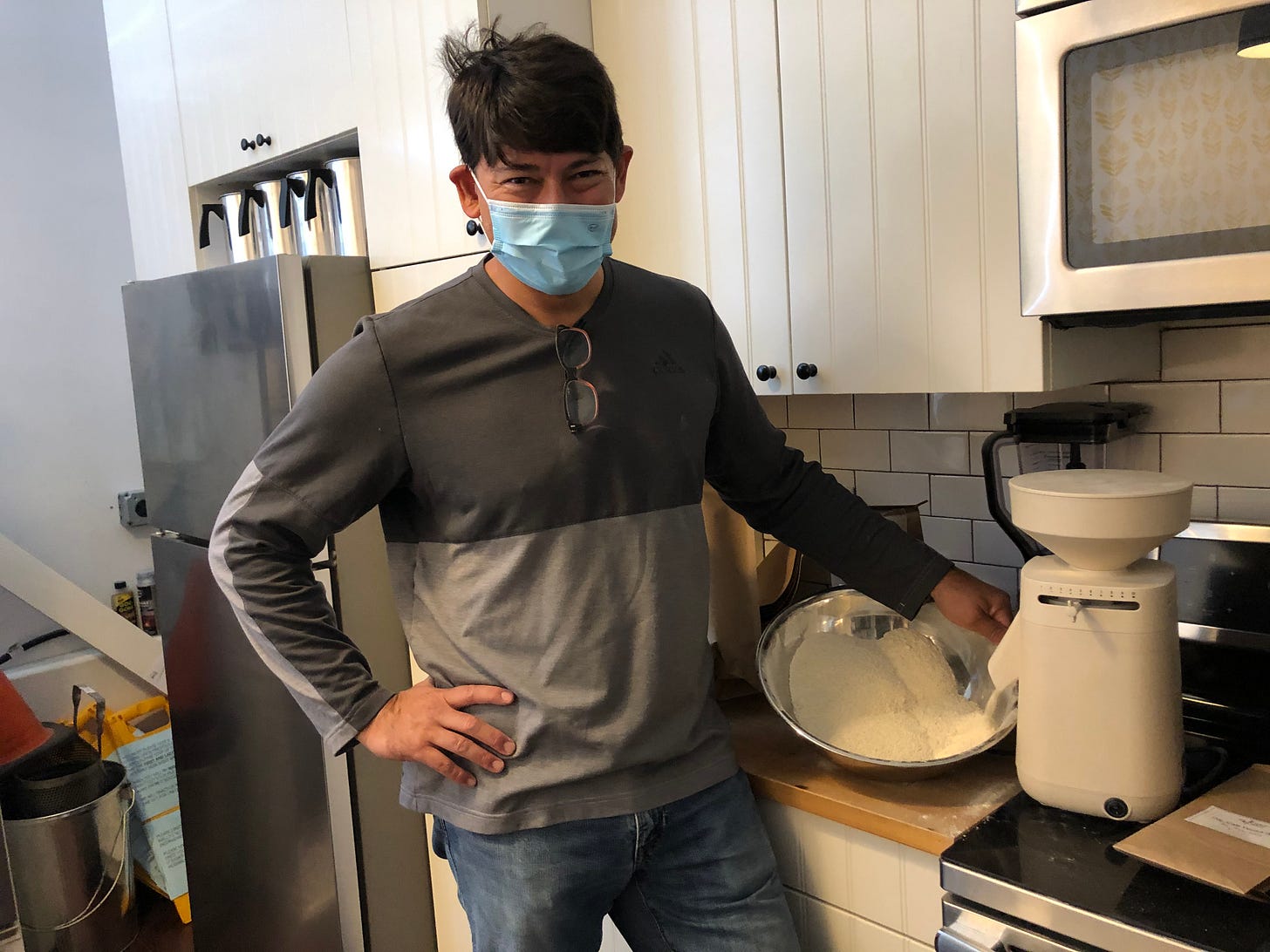

This is the point of view of Roe Sie, and it’s well worth considering. He’s the charismatic founder-owner of The King’s Roost, an artisan flour and grain supplier and, in pre-pandemic times, a popular cooking school in Los Angeles’ historic Silver Lake area.

(You can listen to audio of the entire conversation by clicking on the tart icon below.)

Roe (pronounced “roo”) recently gave me and my friend Patricia Rose a crash course on the perils of highly processed white flour, the benefits of home-milled whole grains, and the magic of using a levain—a sourdough starter—to make all your bread.

Refined white flour, the kind we consume and use in so many of our baked goods, is really bad for our health, he told us. It begins as a healthy agricultural product—wheat berries—that, like an avocado or an egg, doesn’t keep very well once you break them open.

“When you open that wheat seed, you expose all those healthy oils (in the wheat germ) to oxygen, and they go rancid.” This, he said, explains why whole wheat bread often has a bitter taste.

In the late 19th century, flour mills developed the technology to sift out the bran and germ from the flour to create “a lighter, fluffier, less bitter and rotten-tasting flour,” he said.

Unfortunately, while that highly processed white flour offers great shelf stability and baking results, “it’s terrible for your health,” Roe said.

It’s so bad, he added, that between 1906 and 1941, an epidemic of pellagra—basically a niacin or vitamin B-3 deficiency—led to the death of almost 100,000 people in the U.S. “It was its own kind of pandemic,” he said.

The industry’s answer was to enrich flour by adding niacin and other minerals—and later to bleach it and chemically age it, which only made it even more nutritionally deficient.

“People stopped dying, but it didn’t really change the fact that white flour’s not that good for you.” And commercially produced whole wheat flour that you find on your supermarket shelf isn’t that healthy either—it isn’t very fresh and is likely already going rancid by the time you purchase it, he said.

So what’s a home baker to do?

Purchase a home mill, such as one of the German-made Mockmills that Roe sells and swears by, or possibly grind fresh grains in a Vitamix (Roe demonstrates how in one of his videos), or, barring either of these, buy the freshest flour you can and keep it in the freezer.

For those of us who are a little skeptical and aren’t going to buy a mill or Vitamix, at least not right away, what’s the difference between his milled flours and the store-bought variety?

Compared to supermarkets, which are many steps removed from the farm, much of King’s Roost flour comes from Central Milling in Petaluma, CA, an artisanal flour purveyor that buys grains from local farms and supplies bakeries all over the country. When the pandemic hit, Roe was much better positioned to keep supplies of flour, yeast and other goods rolling than were supermarkets. In addition, he sources whole grains from farms all over California.

Many of his customers, who include restaurants, small home baking businesses, and individuals, buy whole grain in 25- and 50-pound bags to mill at work or home as needed, “just like you would when you grind beans for a cup of coffee.”

Can you really taste the difference in fresh-milled versus the store-bought, I asked him.

“I find store-bought bread tastes very chemically to me, and my kids don’t like it.”

They’ve been eating freshly milled sourdough whole wheat bread that Roe makes each week—along with pizza, English muffins and other goodies—for the last 10 years, and they’re a bit spoiled by “Daddy bread,” as they call it.

When Roe bought his son some Wonder Bread once just to see how he’d react, the boy recoiled from the chemical smell when he opened the bag.

Roe himself can’t eat bread made with commercially grown flour and yeast.

If he doesn’t feel like baking one day and buys a pizza from the local pizzeria, he regrets it. “It messes with my stomach. But I can eat sourdough bread that I make at home that’s been long-fermented all day long—no problems at all. And I hear that from a lot of my customers too.”

Many also tell him that they don’t have the same digestive problems with the breads they eat when they visit Europe.

He thinks this may be because of the way our wheat is grown in the U.S., the chemicals used to treat it, and how it’s processed and turned into bread. Most industrial bakers use commercial yeast instead of the slow fermenting that is required to make a bread with a levain or sourdough starter. Roe believes short-circuiting an age-old fermenting practice that exists in almost every culture on Earth may help account for the growing number of people with gluten-intolerance. That and the stripped-down quality of our white flour.

“You take a very high-protein grain, remove everything but the proteins and carbs, add more protein, and then shortcut the process that would allow those gluten molecules to be broken down, and you create essentially an indigestible gluten bomb.”

And the solution? Make your own wild yeast starter. You can watch an excellent video (see above) Roe made to show you how. It has had more than 2 million views and led to many new flour orders during the pandemic, he said.

Even though I’ve been using a starter for years, I learned a few things I didn’t know—like not screwing on the lid so tight when I refrigerate my starter. Apparently, CO2 needs to escape!

In pre-Covid times, Roe offered weekend bread baking and other DIY classes at his store. When he accompanied his wife Trish, a film and video director, on location, he would offer three-hour workshops that ran the gamut from the history of wheat to making bread.

“We do everything from selecting the grains to milling the flour to mixing the dough to baking the bread. We even make butter,” he said. “It’s the only class that I’m aware of where the students mill their own flour.”

He hopes to start offering classes again when it’s safe to do so—and maybe he’ll post some online before then.

How did he get started on this life as a grain entrepreneur, baker, teacher and flour evangelist?

About 10 years ago, Roe decided to leave a career as a human resources exec to become a stay-at-home dad to his two children, now 12 and 17. Along the way, he became an urban homesteader, raising chickens and tilapia; making soap and candles; pickling and fermenting; and baking bread.

One day, a friend suggested that since Roe was making bread, he start milling his own flour.

“ ‘I don’t have room for a mill and a donkey,’ ” Roe recalled telling his friend. But the friend turned him on to electric milling machines. “He said, ‘It’s like a coffee grinder, but it’s got a stone inside instead of a burr grinder.’ So I bought one and ever since I”ve been milling everything—all the flour (I use) is 100% freshly milled from living whole grains.”

In addition to yeast and flour-milling videos, The King’s Roost website has others on making sauerkraut and cold-process soap making, and one from wife Trish (aka, “the crazy chicken lady”—see below) on how to make your pet chickens cuddly (hint: one tip is “channeling your inner rooster”).

It’s hard not to succumb to temptation and order a beautiful wooden-cased flour mill for almost $500 after listening to Roe sing the praises of home milling for the better part of an hour.

“You think they’re a good buy?” I asked.

“They pay for themselves,” Roe said.

He’s figuring in buying a 50-pound bag of organic whole wheat berries that will last forever in the freezer, cost less than a dollar a pound, and provide fresh flour every time you mill them.

But honestly, I don’t have extra freezer space, and I can salve my conscience about buying some shelf-stable organic white flour (albeit the freshest available) from Roe, because I also purchased some organic pumpernickel rye meal (the coarsest grind of rye) and a medium organic whole wheat. My friend Patricia bought the same flours.

Patricia, a blogger, teacher, chef and ardent home cook who was the subject of a previous post (click here to read and listen), made a sourdough country loaf and planned to make a deli rye.

Inspired by Roe, I made a challah without commercial yeast using a starter and a sourdough pumpernickel rye incorporating all three flours.

With Thanksgiving right round the corner, I’m wondering how pumpernickel would work in a pumpkin pie crust.

And I’m still thinking about that mill.

Thanks for checking out this edition of RuthTalksFood. If you haven’t already, please sign up to receive future posts in your in-box.

Your pumpernickel rye looks amazing!!!